Spilling Tea: The Startup Security Trap

Usually, “spilling tea” implies gossip—secrets let slip, truth laid bare. But in this case, it’s neither funny, juicy, nor dramatic. It’s devastating.

The breach of Tea, a verification-first dating app designed for women and nonbinary users seeking safety and authenticity, wasn’t just another leak in the never-ending flood of exposed data. This was a betrayal. And not just by hackers. A breach like this happens because of economic incentives that point in the same direction: risk offloading, security shortcuts, and ultimately, public harm. In a future post, I’ll talk about this concept more broadly. Today, let’s focus our attention on this specific breach.

This post isn’t about shaming the team behind Tea; plenty of others have and will write about that. This is about examining why things so often end this way. Why a service intended to provide trust ends up breaking it. Why doing security “right” from day one can be a death sentence for a startup. And why, time and again, the people with the least power are the ones who pay the price.

Let’s talk about how we got here.

Tea Is Essential

It’s easy to look at a dating app and roll your eyes—yet another startup chasing hearts and VC funding. But Tea wasn’t trying to be another Tinder. It was built around the need for safety: a space where women, nonbinary people, and other marginalized groups could verify the identity of their matches. No fake profiles, no catfishers, no bots. Just real people, proving who they were.

There’s a real market for Tea—a need that deserves its own piece, and I’ll likely return to it later. Today, though, I’m talking about the economics behind the breach itself.

Without going into that level of detail, suffice it to say that, in a digital dating world full of anonymous manipulation, a product built on verification makes sense. Especially for people who are often targets of harassment or violence. Apps like this aren’t frivolous—they’re protective infrastructure. The kind of service that exists precisely because the default internet experience isn’t safe.

But that sense of safety works only if the platform itself can be trusted. And that’s where things broke down.

A Bitter Truth: The Economics of Trust and Speed

For a startup, speed is survival. If you can’t grow fast enough to show traction, you don’t get funding. If you can’t roll out features quickly, users don’t stick around. If you don’t scale fast, someone else eats your lunch.

Security, meanwhile, is slow. It costs time, money, and people—three things early-stage companies never have enough of. They barely have enough to keep the lights on. Security means building controls that don’t drive growth, but do create internal friction. It means saying no to shortcuts. And sometimes, it means building the unsexy plumbing nobody sees—just so you don’t bleed out in six months. In short, it takes money away from keeping the lights on.

And here’s the kicker: if a startup doesn’t invest in security and cuts corners instead, it can still succeed—at least in the short term. Companies are effectively forced to bet they’ll avoid being breached long enough to grow into security they can afford. The costs of that decision are offloaded to someone else. The users. The public. Whoever gets caught in the breach fallout.

Doing the right thing early often means dying before you get the chance to help anyone. And, as we’ll see later, some startups don’t simply bet on speed—they completely skip the basics. In Tea’s case, what went wrong wasn’t just a tough choice. It was a total failure of execution.

But first, let’s talk about those choices—and why even some bad ones can be rational in the moment.

Startups Brew Security Issues

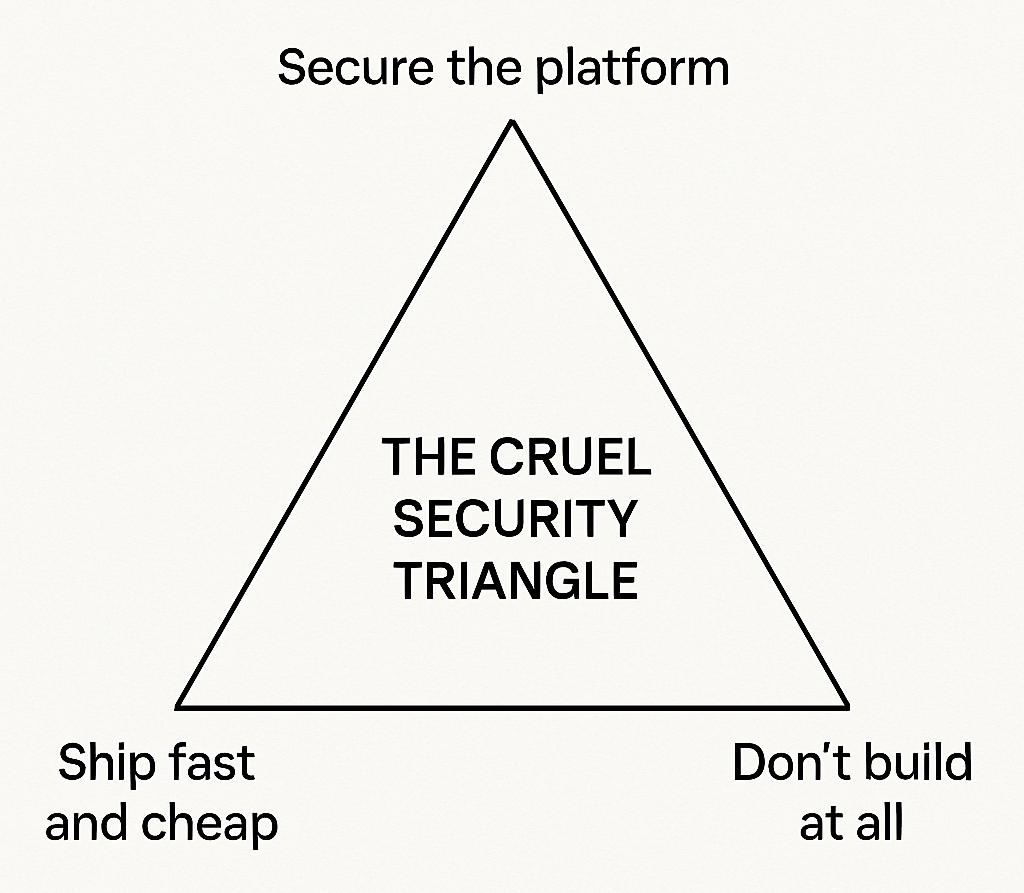

The problem of inadequate security at young startups isn’t unique to Tea—it’s systemic. Early-stage startups are caught in a cruel triangle:

- Secure the platform → risk starving before you grow.

- Ship fast and cheap → risk devastating harm.

- Don’t build at all → leave real needs unmet.

This general idea isn’t new. Wendy Nather coined the term “Security Poverty Line” more than a decade ago to describe this very problem: the point below which organizations quite literally can’t afford to defend themselves. It’s not about negligence—it’s about resource constraints so severe that even basic protections are out of reach. Even founders with the best intentions are pulled toward the corner that leads to harm. Why? Because the incentives push them there. Investors don’t ask, “How secure is your stack?” They ask, “What’s your CAC-to-LTV ratio?” Feature velocity matters more than data integrity; MVP doesn’t stand for “Minimum Viable Protection”. This is why most early-stage startups inherently operate beneath the Security Poverty Line. Even when they understand the risks, they’re forced to make security trade-offs because there simply isn’t enough money, staff, or time to do it right.

This inherent economic scarcity is what gives rise to what I call “Minimum Viable Risk”—the amount of security a team hopes it can get away with while staying alive long enough to grow.

The cold logic of the market punishes companies that slow down for safety. Meanwhile, the companies that offload risk often win—until they don’t. And many of them do avoid rolling boxcars in that critical early stage, growing up to be closer to doing better security...eventually.

What Spoiled the Tea Party

I said this post wasn’t going to be about shaming. But that’s not entirely true. Some of it is in order here, because Tea did worse than it should have, even given typical early-stage constraints.

Tea required identity verification to give its users confidence in who they were matching with. That verification meant uploading photos of government ID—one of the most sensitive pieces of personal data possible. That’s what took this breach from bad to catastrophic.

This wasn’t some sophisticated, untraceable exploit. The Tea breach happened because a cloud storage bucket—used to hold thousands of selfies and driver’s licenses—was left wide open to the internet. No authentication, no access controls, not even basic obfuscation. Anyone with the URL could browse it like a photo album.

And inside that bucket? Verification images that users had been promised would be deleted. Photos submitted years ago. A trove of personal data that didn’t need to exist anymore, but was sitting there quietly, waiting to be scraped. And later, an entirely separate system leaked private direct messages—mundane conversations, confessions, and identifying details—some as fresh as the week of the breach. Those data weren’t just exposed—they were alive.

This was not a case where the cost of “doing security right” would’ve doomed the business. This was a failure to do security at all.

It’s the difference between skipping building a bank vault and leaving the front door wide open with a handwritten “please knock” sign. Even the most aggressive move-fast-and-break-things mindset doesn’t explain away this kind of negligence.

Tea said it kept the data for cyberbullying investigations. Maybe. But they could have been upfront about that, instead of implying deletion. And even then, that doesn’t explain the lack of even the most basic access controls, or the years of unnecessary exposure. And if you build an app for people who are often harassed, outed, or stalked, your responsibility doesn’t stop at intent. It lives in execution.

What makes this breach especially galling is that it was about trust, safety, and the failure to protect those who needed it most; the very people drawn to Tea were already navigating personal risk. They trusted the app because it promised protection—because it asked them to verify their identity, to take a leap they wouldn’t take anywhere else.

And it egregiously violated their trust. In so doing, it amplified harm for people who turned to the app precisely because they’d already been harmed elsewhere.

Tea’s Security Didn’t Have to Be Overly Taxing

This breach won’t be the last. And unless something changes structurally, the next app built for a marginalized group—survivors of abuse, trans communities, undocumented workers—will face the same impossible choices.

We need stronger rules. If you collect ID, you should be required to delete it. If you’re breached and lied about your data retention, enforced liability should follow. If you build services for vulnerable populations, there should be real standards for how you secure them.

That’s not about punishing startups. It’s about making safety survivable. About building incentives that reward doing the right thing early, not just fast.

We’ve built regulatory frameworks for this in other spaces—financial services, healthcare, even food. It’s time we treated personal data like personal safety—because for many users, it is.

Reading Tea Leaves: We Can’t Keep Outsourcing Harm

Tea wasn’t trying to exploit its users. But intention isn’t the same as impact. And economic incentives don’t care about intent.

What happened here wasn’t just a technical failure—it was a systems failure. A market failure. A structural inevitability. Until we change the rules that make these outcomes so common, we’ll keep watching the same pattern play out: New app. Big promise. Silent shortcuts. Breach. Apology. Repeat.

We can do better than that. The people who most need apps like Tea deserve better. And if we don’t change the rules, we’re all just waiting for the next spill.

Comments ()